When a main-sail rips it doesn’t sound like a pair of slacks tearing. It sounds like something profound in the world is shredding. Imagine the sound of love being shredded. Imagine the fabric of faith ripping. It strikes a primordial tone, like the explosive buzz of a rattlesnake.

a decades-old main ripping is not surprising, but still sad

My buddy Lou and I headed out in the early afternoon toward Smuggler’s with a forecast of 10-20 knot winds. Lou is a novice sailor, but an otherwise experienced boater, having been deep sea fishing far off shore. He’s also a diver and surfer that has crafted his own spear-gun. In short, he is ideal crew for The Creamy Pint because he hasn’t been corrupted by fancy shit like pressurized water, an electric windlass, and other niceties. It’s just like Tolstoy wrote, “Pierre had learned. . .that happiness is within him, in satisfying of natural human needs, and that unhappiness comes not from lack, but from superfluity.” By the way, if any of you have a line on a tiller auto-pilot, let me know.

Out of my extensive arsenal of head-sails I chose a No. 3 jib and we pointed as close to the east end of Santa Cruz Island as we could and settled into a nice 17 knot breeze. I scampered on deck and deployed the main sail’s only reef. The swells and wind were bigger than predicted and it wasn’t long before we were into the shipping lanes. We were heeling around 20 degrees, sometimes 30 with a puff.

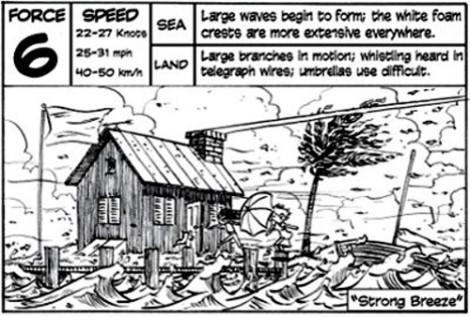

The seas built and I heard the enchanting sound of a hum in the rigging. The little boat was muscling into the weather like a scrappy prize fighter. Waves became harder to casually take and green water started breaking over the bow. There was a slap-stick moment when a saucy wall of water sprung toward us and I ducked, but Lou caught it right in the face. The little outboard, though elevated as much as possible, was getting dunked. It didn’t look happy at all and I non-chalantly tried to fire it up while Lou took the tiller. It started, gurgled and died. Near Frenchy’s Cove I decided to tack so we could skirt around Rat Rock. We were close-hauled in something very close to beufort scale-6.

more than force 5, less than force 7

And having a blast.

Until that sound. A tearing, what the fuck is that, oh shit it’s the fucking main ripping, sound. I sprung to the halyard and had the sail down so fast it was still tearing in my hands as I doused and bound it to the boom. Smuggler’s was about five miles dead into the darkening weather and night. Lou and I chatted a bit and decided to head back to the marina. Getting to Smug’s (straight in wind) with just a head sail wasn’t something I wanted to do, and I was suspicious of the abused, little motor and didn’t like the idea of sailing off anchor with only a head sail. So under a 35 year old No-3 jib we bore off to a broad reach and headed to the barn.

The handheld G.P.S. registered 6.9 as we surfed waves. The seas were rough enough that the gimbaled cabin lamp came out of its rocker-arms and spilled paraffin on the cushions. The seas were rough enough that the oak table leg broke. The rough seas broke the pig-tail and the boom thudded on my shoulder. The seas broke the lid of the cooler.

I said, “Lou, you’re a surfer, surf this shit. Let’s see your chops! And, don’t worry, that little motor will fire up soon as get in the marina, it just needs to dry out a bit.”

Near midnight we passed the break-water with dying wind but big swells. The motor fired up, but we realized when I dropped the jib that it wasn’t doing anything. The prop spun languidly, failing to provide thrust. I set the Hysenberg Compensator to level 12 and I disabled the phase-inhibiter, but the little motor still didn’t have any teeth.

“Bah, we’ll sail into the slip with just the jib, Lou.”

As we worked our way toward the slip some guys in a 22 were zipping around the marina. They were having a blast and it made me think of beginner’s aversion to sailing at night and how misguided that is.

The light wind died off and what little bit there was blew straight from my dock. We spent forty minutes trying to work our way into the dock before I took a nearby end-tie, which I learned the next morning a 100’ power boat had reserved. Walk a mile in my moccasins before you call Harbor Patrol, fuckers.

dying wind, but decent swells and the moral of the crew is undaunted

Post script:

The next day Lou came down and helped clean up the boat. Mike came down and side-tied his dingy to the Pint to get her back to the slip.

These puppies have two or three speeds and will take up the line as your grind it in. They are PRICEY.

These puppies have two or three speeds and will take up the line as your grind it in. They are PRICEY.